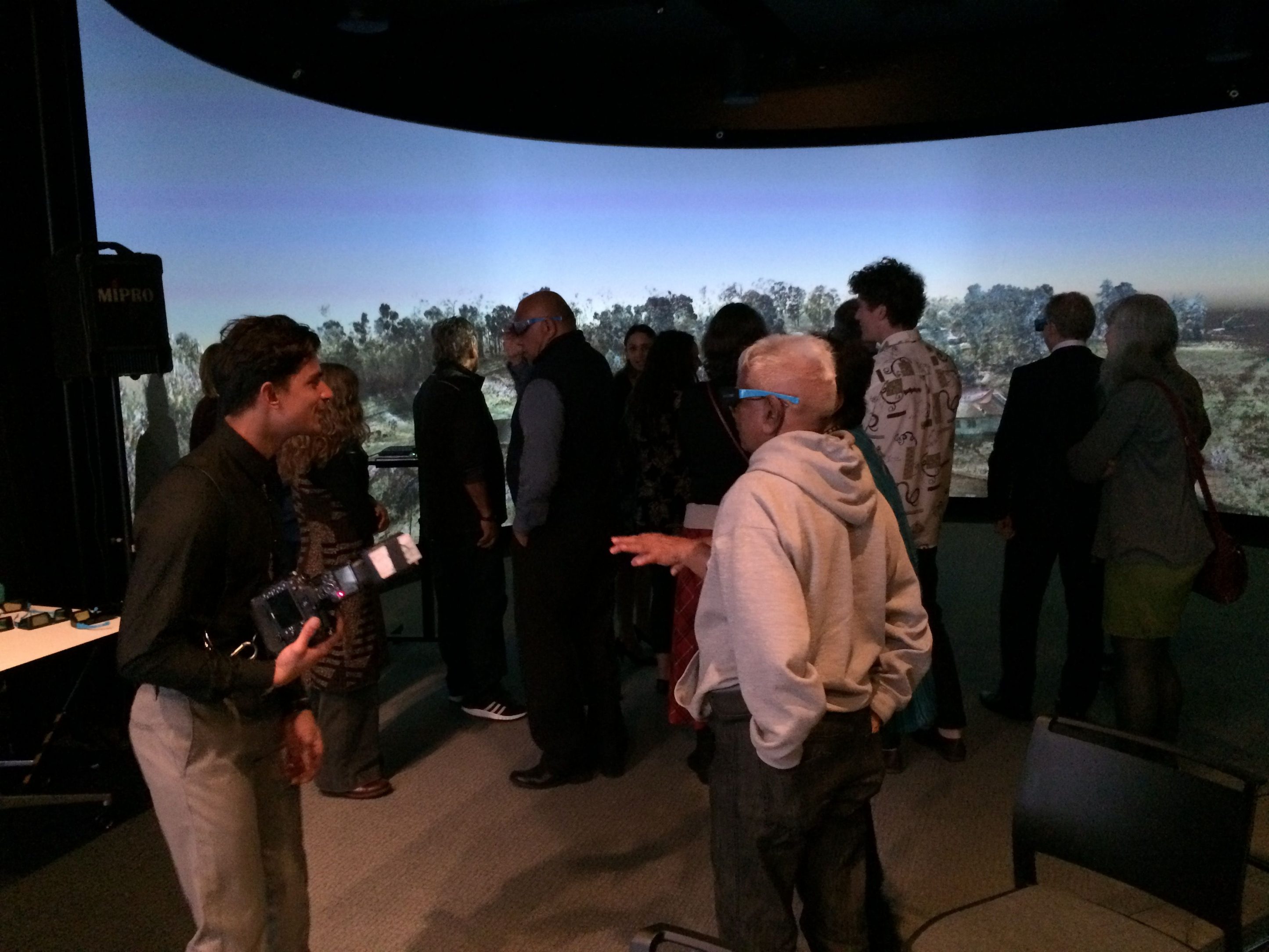

In April 2017 former Aboriginal residents of the Wandering Mission, Curtin University researchers and students met at the former mission site to engage and discuss Survivors’ experiences and possible futures for this place. The remembrances were confronting, affecting for both the narrator and listener, and their effect was amplified by the places of recollection. While the mission sites reek of trauma, they are also a homeland and a place where Survivors believe their distress can be healed.

In order rehabilitate this place, into a place of healing, a steering committee was created for the Wandering site. This comprised of varying stakeholder groups, namely Bringing them Home WA, the Southern Aboriginal Corporation, Stolen Generation Survivors and Curtin University researchers. The steering group sought to clarify the complex notion of ‘health’ and ‘healing’, beyond the function of individuals, broadening the definition to encompass connection to land, cultural and familial ties, cultural security, and the impact of child removals, cultural disruption and racism on the overall community (Newton et al. 2015.Otim et al. 2015). This more holistic definition, coupled with extensive background research into global Indigenous case studies on the effects of displacement laws and intergenerational trauma, comprised the contextual base for the next stage of consultation with community members.

Extensive consultation was conducted through design workshops and in-depth informal conversations. From this process ‘memoryscapes’ were mapped to help formulate a vision for the future of this place and a framework was established against which the proposed outcomes would be assessed. Continued community engagement ensured the community discussed issues and made decisions for future stages of the project.

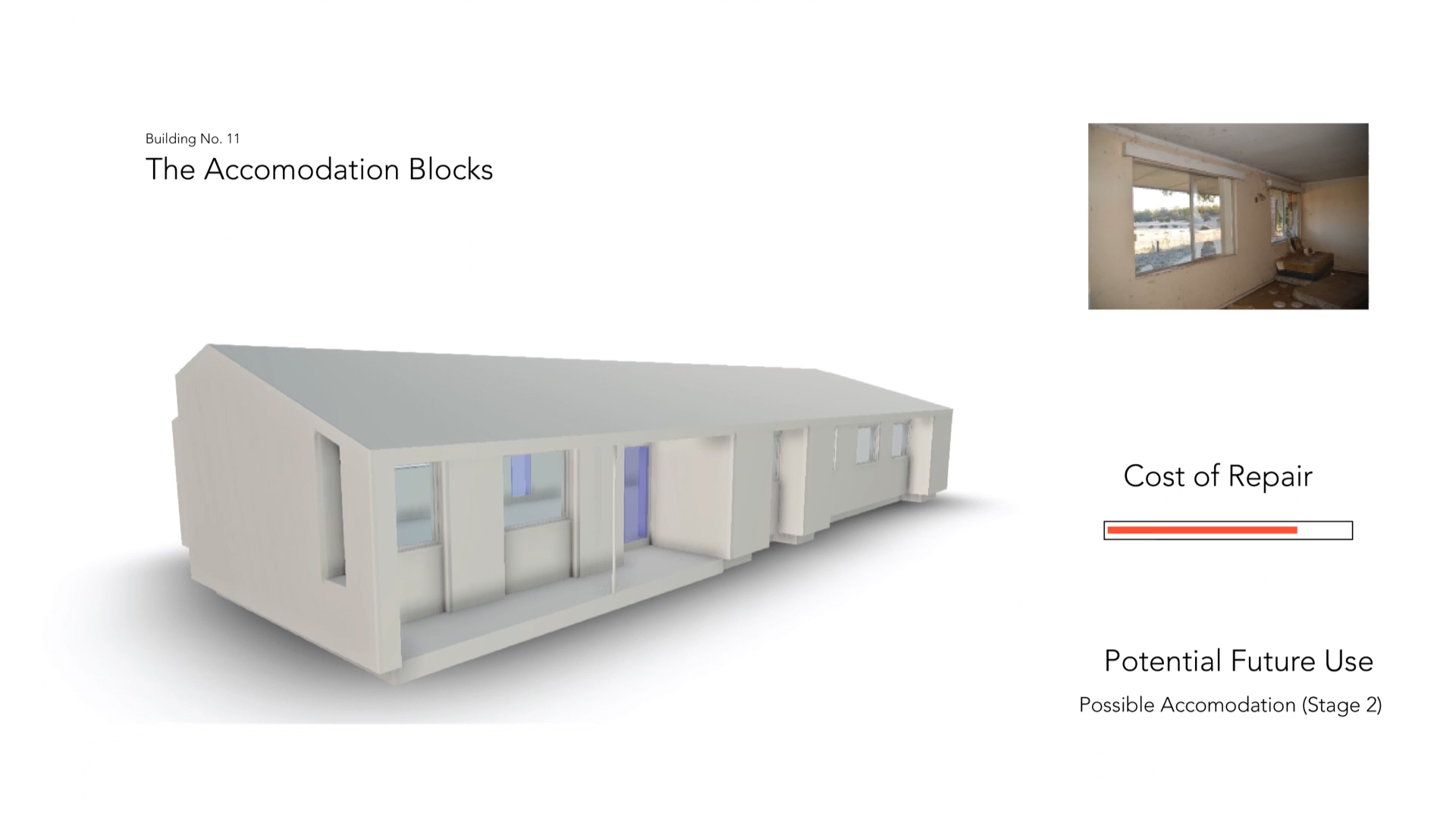

An in-depth contextual understanding of the physical, emotional, and ephemeral qualities of this place lead to a draft rehabilitation plan that was Survivor lead, emotionally and economically sound. Essential to this rehabilitation plan was an audit of the built environment, documenting the physical, social and economic value of each building allowing works to be prioritized by the community members. Such works were planned within a staged framework (Tiwari et al. 2017);

- Stage one is reactivation. Initial repairs carried out allowing some Survivors to return.

- Stage two is increasing activity and occupancy, emphasizing activating spaces that empower Survivors spiritually and practically.

- Stage three aims to expand the Wandering Mission’s relationship to the wider community through a Visitors Centre, and opportunities for public to visit and learn.

- Stage four sees intervention into spaces that are extremely sensitive to Survivors and/or costly to redevelop.

The Curtin team of researchers and students, were involved in completing early collaborative works such as the draft building condition report, draft master plan, digital scanning and modelling of the site and buildings. The cooperative model has potential for future expansion through a digital platform giving a virtual identity to the community allowing for further awareness raising opportunities nationally and globally. The project has also attracted further pro bono work and a commitment from Mercy Care to assist stakeholders with the mission redevelopment (Morrison, 2017).

Establishing Healing Centres at mission sites in which Survivors have direct input in the planning and rehabilitation of such places is empowering and the knowledge shared through this process builds capacity on both sides. This project is built around a framework that recognizes cultural healing and a connection to the site as homeland, strengthens and promotes Aboriginal culture, stimulates financial independence and engenders a sense of ownership and community.

Through dialogue with and cooperation in, design workshops with members of the Stolen Generation community, it became clear many Survivors were still carrying hurt decades after leaving the mission site. Survivors were at different stages of readiness. Many did not want to visit the site or share their stories, while others were ready to discuss their visions for the site. The realization that not all Survivors wanted to achieve the same outcome for the site was a challenge. They all wanted the site returned to its previous condition, but were divided on how they saw the future of the site. Some buildings carried particularly hurtful memories for some, but not others. Some wanted to promote tourism, others not so much. It is recognised that consultation will be a long, patient process.

This project successfully employed a community-centric approach to produce a sensitive and workable framework for the future use of this space and affirms the intimate links between place, memory, trauma and healing.

“The restoration of the missions is a tribute to Survivors, of the children who were forcibly removed from their families. The work being done is about honouring those children and their families through the healing process of community. We all need to share our stories in community, to take the internal journey and to take part in the process for intergenerational healing to take place.” — Wandering Survivor, Marlene Jackamara, (Yokai, 2017).